Gin and debauchery

+EC1 themes index

Clerkenwell 101

27 As Clerkenwell was originally a suburb outside the London Wall, it was not under the jurisdiction of the puritanical City fathers. Consequently, by the 1600s “base tenements and houses of unlawful and disorderly resort” sprang up, with a “great number of dissolute, loose, and insolent people harboured in such and the like noisome and disorderly houses, as namely poor cottages, and habitations of beggars and people without trade, stables, inns, alehouses, taverns, garden-houses converted to dwellings, ordinaries, dicing houses, bowling alleys, and brothel houses”.

28 Ray Street (originally named Hockley-in-the- Hole) was the infamous area notorious for animal fights such as bear baiting, bull baiting, and cock fighting. In 1709, the bear garden’s proprietor Christopher Preston was devoured by one of his own bears.

29 In Ray Street from the mid-1600s until the mid- 1700s there were sword-fights between men and fist-fights between women (holding half a crown in each fist to prevent hair-pulling and scratching). The most famous fighter was Clerkenwell’s very own Elizabeth Wilkinson, who in the late 1720s published an acceptance of a challenge from Ann Field, an ass-driver from Stoke Newington, telling readers that, “the blows which I shall present her with will be more difficult for her to digest than any she ever gave her asses”. Elizabeth would become known as the “Championess of America and of Europe” in her short, but dramatic fighting career.

30 By the 17th century, the River Fleet had become overused and polluted. Mills, meat markets, tanneries and other industries grew up along the banks, polluting the river with blood, sewage and the occasional dead body. In 1613 Hugh Myddelton created the New River (actually, a canal) which brought a plentiful supply of water 39 miles from springs in Amwell and Chadwell in Hertfordshire. A reservoir was built at the top of Amwell Street. The clean water attracted brewers and plenty of gin distillers.

31 The British government could be blamed for bringing about the gin craze. Ongoing conflicts with the French had lead the government, in 1869, to tax wine and brandy heavily, and encouraged people to look to alternatives that were made in Britain. In fact, no licences were needed to make spirits, including gin. One in four houses were producing a low-grade form of gin that would have been produced in kitchens and sold for pennies. Often the taste wasn’t great though, so turpentine was used to improve the flavour. Hardly the sophisticated botanicals used in today’s gin resurgence. Between 1720 and 1751 gin consumption reached its peak. Clerkenwell adults would drink an average of half a pint of gin a day. At that time over 15% of adult deaths in Clerkenwell were attributed to the excessive drinking of spirits.

32 The problem of gin drinking was the equivalent of crack dens today. It was the ‘Mother’s ruin’ featured in Hogarth’s famous engraving ‘Gin Lane’, which is set on the Clerkenwell borders. Hogarth based the main character on Judith Dufour, who in 1734 collected her two-year-old child from the workhouse, strangled him, dumped the body and sold his clothes for 1s 4d to buy gin.

33 Following Hogarth’s engraving ‘Gin Lane’, an act in 1751 banned unlicensed gin distilling. The regulation of the industry soon saw the establishment of the large distilleries and in the nineteenth century the development of a superior refined clear spirit: London Dry Gin. The distilleries that were to become the household names of Booth, Nicholson, Tanqueray and Gordon were all established in Clerkenwell, which remained at the centre of the gin distilling industry until the 1960s.

Gin Shops in the Regency; some stories about the ‘blue ruin’

The Gin Shop ‘Every street is their tap room’ In January 1816, Worcester businessman Mr S Cohen drank himself to death. He was visiting Mr Moncks, an Evesham Hatter in the afternoon and…

about1816.wordpress.com

Gin Shops in the Regency; some stories about the ‘blue ruin’ • about1816.wordpress.com

https://youtu.be/B6J03q3t9ao

Vic Keegan: How Clerkenwell became the gin capital of the world - OnLondon

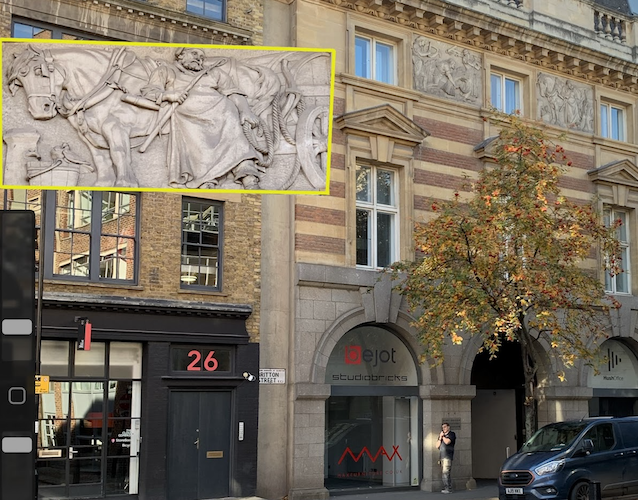

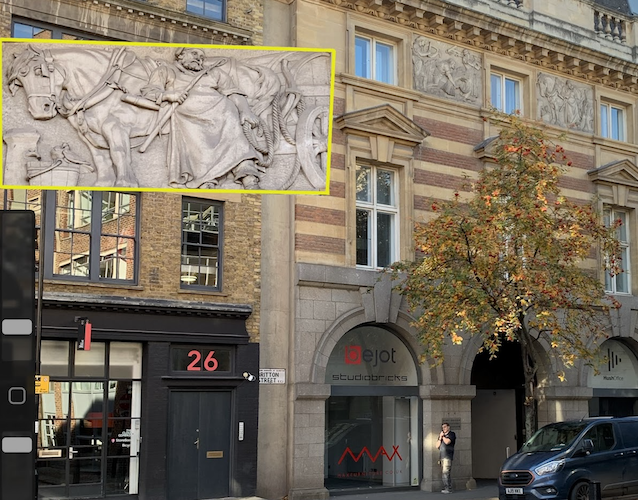

Pause for a while in front of the easily missed friezes in Britton Street, pictured above. They are all that remains of the once mighty Booths distillery, which was at the centre of Clerkenwell’s astonishing relationship with gin. Two other Clerkenwell gin giants, Gordons and Tanqueray, have also long since left the area. So has […]

www.onlondon.co.uk

Vic Keegan: How Clerkenwell became the gin capital of the world - OnLondon • www.onlondon.co.uk

#History #C101